When I was in my early twenties, I spent several months driving a taxi in Austin, Texas. I had been delivering newspapers in the parts of Austin commonly served by taxis, so I knew my way around and how to use a map.

It was a dispatch service. It was possible to get hailed on the street, but that never happened. There weren't enough taxis around to make that notion occur to anyone but the most urban of out-of-town visitors, and there weren't many of those. If you wanted a cab in Austin, you called one. It was the 1980s.

So I would call in my location to the dispatcher and wait somewhere. I may wait for a minute, it may be hours. I had to wait to be told where to pick someone up and where they were going. I had a meter in the cab; out-of-town trips were also possible (I made several late-night trips with inebriated soldiers back to Fort Hood, about 90 miles north) and were sometimes negotiated by the dispatcher on the phone when the person called and paid in advance.

The graft was rampant. Drivers who "tipped" the dispatcher made the most money. I was not among those (I was young and stupid). This made it a subsistence existence, mostly helpful because I had a car I could also run errands with. This unskillful relationship with the dispatcher also gave me a lot of time to read; I spent hours parked between calls at night. That changed my life.

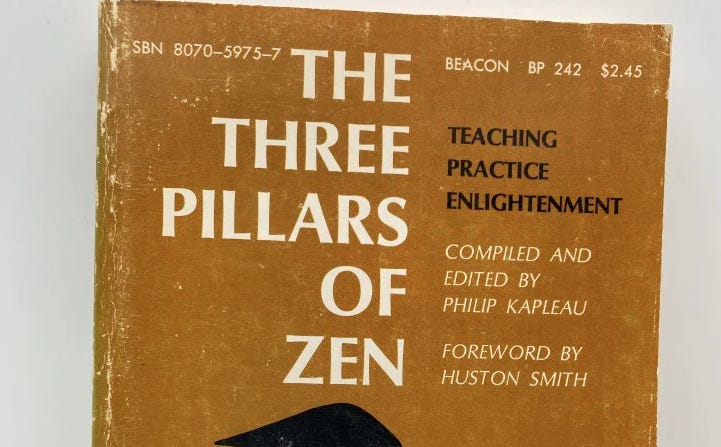

Most notably, I read Philip Kapleau's Three Pillars of Zen. This is a dense and scholarly tome of many hundreds of pages—not an easy read. It was the only book I carried with me while driving my cab. This is likely responsible for why I finished it. It was either read this book or stare blankly out into a dark night for weeks on end.

Also, in the early 1980s, it was one of the few books available on Zen not written by Alan Watts; I had already read all of those (now there are many more, mostly written by people who were students of Zen in the 1980s).

Three Pillars wasn't a pop culture invitation to try on a different view; it was a reference book for Westerners who wanted to understand and study this Asian religion called Zen Buddhism. One approached this work not as an invited guest but as a humble student.

Nothing about it was easy, but nothing about that discouraged me. I took in all four hundred-plus pages while sitting behind the wheel of a 1979 green and crimson Ford Crown Victoria (Roy's Taxi). I didn't know it at the time, but I learned much about the history and lineage of Zen that would make books not yet written much easier to digest.

Roshi Kapleau's book is still a classic, unblemished by its age, and remains a central reference text for Western Zen students. I later realized that reading it from cover to cover was akin to reading the dictionary that way (an act Malcolm X credits as the foundation of his education in prison). Hilariously, on reflection I realize now I was too new to the material to know that I was having trouble following a narrative because there wasn't one!

I just pushed on through, deluded by the notion that this book was so hard to read because the material was so richly full of the novel occult knowledge I craved. Of course, the truth is that nothing about Zen is occult. In fact, quite the contrary, but I digress.

In Zen ritual, much attention is given to endings. There is a certain way to end a meditation period, to end your sitting, to leave your cushion, to bid farewell to your fellow congregants, to conclude a private audience with a teacher, and to leave the meditation hall. There’s a way to stand, to hold your hands, and a correct foot with which to step first when leaving. These ritualized norms have both practical and symbolic justifications, but they all serve to signal that something that was no longer is.

Hospice caregivers know that if you wait long enough, problems take care of themselves. This dark maxim is a comic surrender to everyone’s powerlessness over death, the most inevitable of all endings, but there is also a real kernel of truth to this. Sometimes all you can do is wait for things to happen.

In NYC, riders stand on subway platforms and impatiently peer down the track in the direction from which the train is coming, tapping their toes, pacing in small circles, looking at their watches, as if their impatience can compel the subway to arrive sooner. In automobiles, we inch forward at traffic lights as if this pressures the red light mechanism to cycle to green faster.

What happened to just waiting for the train? What’s wrong with enjoying a comfortable seat in a climate controlled space before the light changes?

We are living in an era of endings. Things are ending everywhere. Institutions are crumbling. Accountability is vanishing. Shame is no longer a thing. Modernity is crashing down around us. We are burning up because we left the range on.

I think of the teenagers in my life and the world they will inherit. They are will be forced to adapt to things coming to an end. Things that people thought would forever be are going to wither and disappear before their eyes, within their lifetimes.

They will invent new ways to cope; I don’t bet against the collective effort of humans, but things are going to have to be very different. No one will have any choice. I’m sorry I will miss that. I am very impressed by the 13-18 year old people I am lucky enough to know.

Some problems will vanish. I often think of the problem of moving horse manure out of New York City before automobiles existed. One had to leave horse manure on the street order to remove it, so one could never get the manure completely out of Manhattan streets. More removal effort made things worse. No one knew how this dilemma would ever be solved. Then it was.

What will being adept at surviving endings look like?

I have been studying a new Zen text called The Eight Qualities of a Great Person. That’s not a good English rendering of the title, though it is maximally faithful to the translation of the words from Japanese.

I would call this text “How to Be a Grown-Ass Adult.” It is newly translated into English, the source material is actually ancient, and it includes commentaries from two important teachers who lived hundreds of years apart. This was the final teaching of the historical Buddha from millennia ago, the final teaching of the founder of my denomination of Zen hundreds of years ago, and the final teaching of a relatively modern Japanese teacher who died a few years ago.

This teaching was what three of my favorite teachers in my religious lineage wanted to end with; it was their ending.

The English book is The Roots of Goodness: Zen master Dogen’s teaching on the eight qualities of a great person, commentary by Kosho Uchiyama Roshi, translated by Daitsu Tom Wright.

What all three of these teachers wanted to teach, finally, as they realized their lives were ending, was how not to act like an effing clown. These teachers saw the end coming for them. This subject matter was what they wanted to perfect while time was running out for them.

As is common in Buddhism, the lessons are in the form of a list, and this is my personal rendering of this list in modern English:

Desire reluctantly and carefully

Know when enough is enough

Appreciate serene environments

Do the hard things that have to be done

Don’t mistake praise for support

Pay attention to silence

Follow your own advice

Refrain from useless argument

What does it mean to desire reluctantly? Does not the heart want what it wants?

Yes, it does, no one can control desire. One controls the pursuit of desires. That’s the important difference.

I have found it useful to learn to sit quietly with my desires. I do this in meditation, and I do this in glitzy Manhattan settings dripping with beauty and wealth. I watch what I want, who my eye is drawn towards, what decisions I am urging myself to make. Why do I want that free glass of champagne? I don’t like sparkling beverages, but I like free stuff. Why does it being free matter?

I want to get all my free stuff. Hmm. Really? Just because it is free?

In meditation, there’s almost always a dialog going on in my thoughts. I am constantly commenting internally on my thoughts, as if there is one person thinking and another person watching and judging. This absurdity arises because of the subject-object dualism of language itself. We think of thinking using language. We are forced to define things by what they are not.

It is possible to pursue desire in meditation. Most commonly, for me, it is the desire to hear the sound of the bell that ends the mediation period.

How many things are done simply so we can say we’re done with them? Cleaning house, going to the gym, doing my filing, paying my bills, washing the dishes, doing the laundry, and making my bed are all things I do so that they get done. I rarely invest effort into enjoying doing them. I want the ending more than to enjoy the doing. I want free stuff. I don’t enjoy taking care of my life. I want to be done.

These are the motives of the wise sage within me? This “be done” voice sounds like it belongs to a slacker living in Mom’s basement. This is why desires do not overwhelm my decisions. I don’t have a lot of respect for the part of me that desires—he eats Cheetos and complains about his strangely orange genitalia later.

I take note, I pay attention, but I don’t place bets on my desires. Chances are another part of my mind has a better idea.

We want something to end when we have had enough. Knowing enough is enough is the antidote for greed. What is enough?

In my mid-60s, this is the question that looms larger than any other. What is enough?

I often find myself giddy with ordinary happiness these days. I enjoy my work, my home, my friends, and my leisure time. I live in the greatest City in the world, I have money in the bank on the day before payday, and I have a long list of books I want to read, projects I want to work on, and things I want to learn.

If this isn’t enough, I don’t know what is enough. That isn’t rhetoric. I mean that. There’s no feeling that goes along with “enough.” Enough is defined by exclusion. It is the absence of both lack and excess.

I, that thing that knows things, is built on the notion of a fundamental search for certainty and substantiality that we just don’t find anywhere. This is what every teaching in Zen ultimately points to. We are fish swimming in search of water.

I will never feel like I have enough.

I will have to accept just knowing that I do.

That’s being a grown-ass adult.