On the union of oneness and separation.

I have returned, like visiting an old friend, to one of the most ancient and fundamental of Zen Buddhist texts, The Sandokai. It is a poem, a couple of typed pages long, written by a Chinese monk from Guangdong province in southern China in the beginning of the eighth century (the 700s). It is generally recited at the end of formal multi-day meditation intensives, and zen writers generally address it when they hear the proverbial clock of human life ticking. Hello.

Like most texts written in one language, interpreted in another, and then with interpretations getting translated to yet another third, or fourth language, it can be difficult to study. Further, the text itself directly cautions against grasping, clinging, or being certain of any understanding of it, or any other concept.

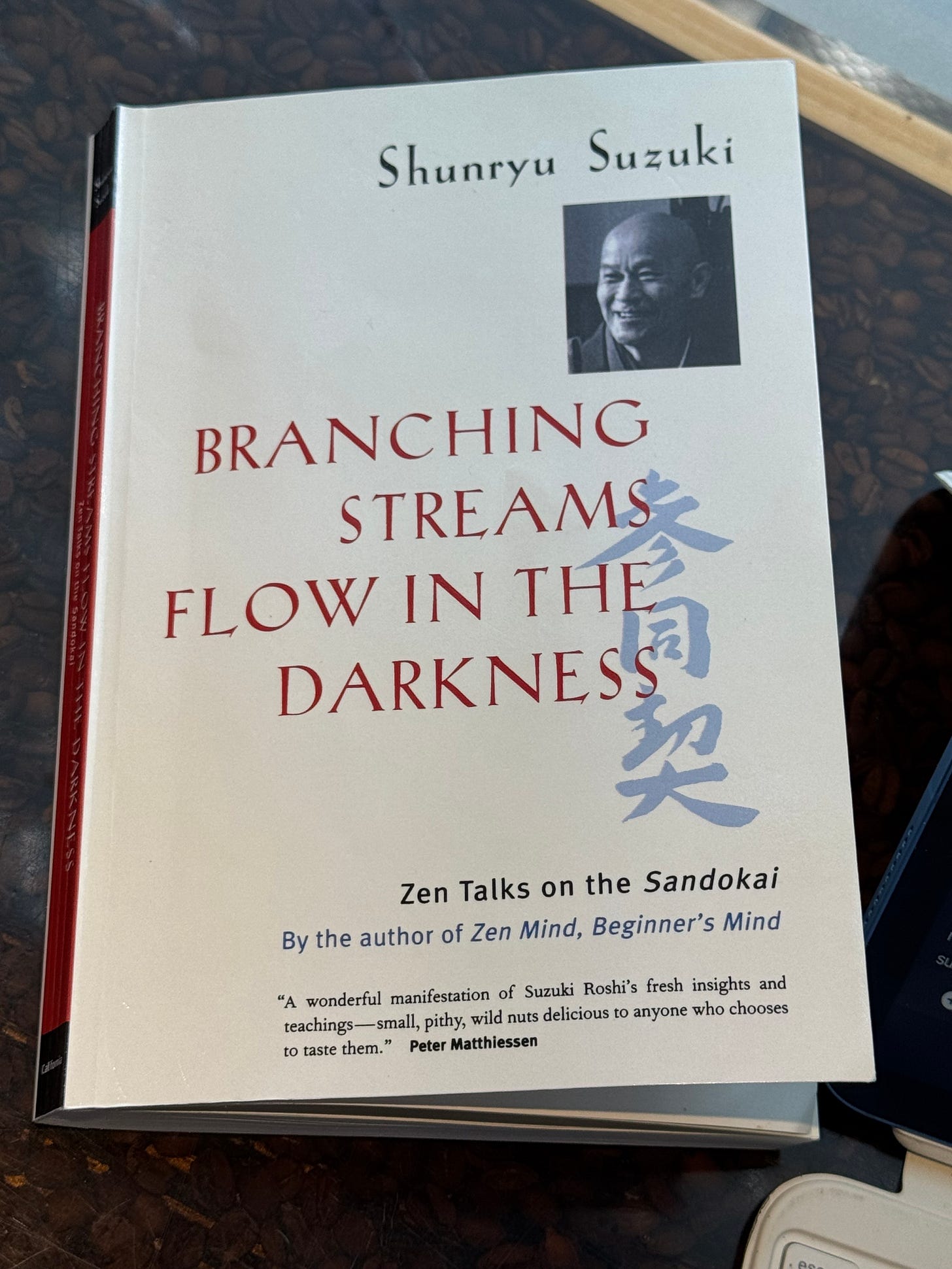

Specifically, I have turned to someone in my religious lineage, Shunryu Suzuki, founder of the San Francisco Zen Center, for commentary. The book “Branching Streams Flowing From The Darkness” is a compilation of talks he gave in 1970, almost the last year of his life. Suzuki Roshi is my dharma Grand Uncle, a peer of my Dharma grandfather, Dainin Katagiri, who founded the Minnesota Zen Center. My teacher, Steve Hagen of Dharma Field, also in Minneapolis, was Katagiri Roshi’s student. Buddhists fret about these associations because we all want to trace our lineage back to the historical Buddha. Buddhism is passed from human being to human being, and always has been. I can trace mine all the way back too.

Suzuki Roshi was particularly suited, in my view, to instructing the collection of hippies and bohemians who flocked to his teaching in 1960s San Francisco. This isn’t because he particularly liked or approved of their lifestyle, he didn’t. He succeeded because he followed the path these teachings laid before him. Suzuki was actually a typically uptight and conservative Japanese priest, with the manners and attitudes one might expect from the archetype.

I believe he took the failures of Japanese zen to respond effectively to the Imperial Japanese fascism that led the country into WW2 as a wrong he needed to make right. The story isn’t very widely told, but Kamikaze pilots took their inspiration directly from institutionally-perverted zen teachings. I suspect when he was faced with the resistance and opposition internally to lecturing long-haired and often unwashed stoners he accepted this as his karma and put forth his best effort to bring them the teachings.

Of course, he succeeded, wildly beyond anyone’s expectations. San Francisco Zen Center is now regarded as a world-wide locus of Zen Buddhism, really second only to the founding temples in Japan. That all started with lectures to stoned hippies. You may or may not be surprised that I consider SFZC to be overly conservative now, stuffy, and a challenging place for an unorthodox student to find a home. I started there, but I left quickly, alienated by all the bowing and grim aloofness of it’s students.

This irony actually demonstrates one of the fundamental teachings of the Sandokai, and zen itself: it is not always so. That is, nothing persists as it appears to be. Everything is in the midst of change from each moment to the next. But, this very profound truth isn’t the point of the text.

When one begins a disciplined meditation practice, ti isn’t terribly unusual to have a particularly type of realization that people often confuse with “enlightenment.” People have a number of terms to describe it, but it is that moment when one realizes, for whatever reason, that everything is interdependent and connected, nothing is truly separate from anything else, the world is all one interdependent system.

This is the basis of the joke about what Buddha said to the hot dog vendor — make me one with everything!

The Sandokai says “not quite.”

That experience is profound, I have had it, more than once, and you do emerge from it with a feeling of being very grounded and serene, but this is not the end all and be all it is often thought to be. Why? Because we are actually also all separate beings with our own paths to follow. That is just as “true” as we are all interconnected beings and indivisibly part of one system. Both of these seemingly mutually-exclusive ideas are equally true.

How can that be? Because the fault lies with the idea that there is something to figure out. That there’s this thing, that we are all connected or that we are all separate, that needs to be discovered and understood. No, there’s not. Both things are true, at the same time, despite the fact that they are conceptual opposites. That’s the problem with concepts, and with ‘thinking’ your way to ‘seeing.’

Consider particle physics and the questions of whether light is a wave or a particle. Sometimes it acts like it is everywhere at once, like when you flip on the lights, other times is it definitely a thing, a string of localized points, like when you do the two-slit experiment. It isn’t that light, and photons, flip back and forth to confuse us. It is that reality can’t be understood by thinking and talking about it. We are like fish searching for water.

Light is both a wave and a particle, as are all the other things that constitute reality. Even mathematics can’t approach these truths without the use of imaginary numbers like the square root of negative one. There isn’t a number which can be multiplied by itself that gives you negative one. Yet, this term is absolutely essential to describe reality mathematically. None of the equations work without it.

Now, explain to me what an imaginary number is. That’s also what enlightenment is.